Imagine having an hyper realistic “SimCity” simulation that would show us the best way to rule a city. Wouldn’t that be great? What if our SimCity’s president was an AI? What would it try to optimise? What would the citizens of the city try to optimise if they were AI too? In this post, we will explore how such a simulator could work.

Table of contents:

The Role of the Government

Societies are in a constant fight against corruption. A constant conflict between its values and its members’ self-interested goals. The role of the government is to align the two by enforcing rules that ensure that a selfish acting agent is simultaneously an altruistic acting agent benefiting society.

Driving gives us a quick concrete example of this. If everyone was to drive at a moderate speed and keep a safe distance to the car in front, everyone would reach their destination faster. There would be more time for drivers to smoothly adjust their speed in response to the car in-front, and consequently, less stop-and-start traffic jams and fewer accidents. Unfortunately, if everyone is driving responsibly it would be incredibly easy for one individual to go rogue and break everyone’s safety distances by going in between other cars to reach his destination even faster. This individually rewarding behaviour is harmful to society. To inhibit it, governments created speed tickets which if high enough should ensure that the selfish driver would want to travel below the speed limit, optimising its goal of reaching its destination as fast as possible whilst avoiding expensive fines, which in turn, is aligned with the society’s goal of reducing the total travel time for all its citizens.

The Need for Competition Amongst Governments

Governance is generally a service provided by our governments. Some people pay a high price for this service and they don’t get much value in return. They wish to change their service operator but changing governments, if possible, has a big cost as it often requires people to move to a different nation. Whenever there is a big monopoly people’s choice is limited and the quality of the service provided is lower. Is there a way to give more options to the people?

Paul Romer, Nobel laureate in Economics, defends the creation of many independently governed cities (called charter cities) as a way to explore and find better governing rules. In summary, a charter city would have a charter (a set of governing rules) and it would be built on a piece of uninhabited land. People would be allowed to move in and out of the city as they please. Setting rules on uninhabited places should lead to a much easier and faster process than to change rules on populated places where many would have different interests and opinions regarding those rules. The idea is to have a high number of charter cities, with different sets of rules, competing for citizens. The most successful cities would naturally expand while the less successful would adapt or die.

Paul argues that the biggest barrier for raising the living standards, in this century, is not scarce resources nor limited technologies but our limited capacity to discover and implement new governing rules[1]. These rules need to be adapted as the scale of our cities and available technologies improve. The set of rules that enable citizens of a small village to live in harmony will be very different from the rules that allow millions of us to live within dense cities with access to powerful technologies. We recommend you watching Paul’s TED talk about this subject where he builds a very convincing case for charter cities and points to a few extremely successful examples in our history. Another fascinating project is the Seastanding[2] that wants to build competing governing cities that float on international waters.

Whilst there are hundreds of thousands of new businesses being born and dying every year there are not many changes in the set governing rules we have today. The inertia to change the existing rules makes sense, citizens (and their business) are more productive in a world where the rules are stable and allow for long-term planning. But this means we are exploring the space of profitable business plans at a much higher pace than the space of efficient governing rules.

No computer experiment could ever replace the experiment of trying it out on an actual city. However, there is an infinite amount of rules we would like to explore and building new cities is restrictively expensive. Cheap computer simulations could tell us which experiments are more likely to succeed. It would be a valuable tool for governing innovation, a way to speed up mankind’s search for a set of governing rules that lead to efficient and incorruptible societies. The remaining part of this post will discuss the main principles on which these society-simulators could be built on.

The Roots of Corruption:

how citizens get misaligned with their society

One might think that the major cause of problems in society is a lack of ethics from their citizens. Could we fix things by simply educating our children to be moral according to our society’s values? To do good (according to society’s ethics) in all situations despite their individual goals? To respect the speed limits not because there could be a fine to pay but because it is the right thing to do? We will argue that it is indeed important to teach ideology and moral to future generations but a society where the goals of individuals are not aligned with the goals of the society is generally an unstable system that will eventually disappear.

There is a universal truth that helps us describe stable systems: better things at surviving and self-replicating will increase their numbers faster than their less capable peers. When these things (replicators) are competing for a common limited-resource, the less capable replicators will eventually disappear leaving the more capable peers to dictate the world’s future. The study of different types of replicators (such as genes, ideas, business plans and behaviours) and their specific mechanisms for replicating make up the core foundation for different research fields (such as biological evolution, mimetics, economics and sociology). A society can be defined by the behaviours of its members, and studying how these behaviours propagate will be key in finding stable societies (stable with respect to its values/ideology).

We’ve been assuming that society’s members are self-interested but we haven’t yet defined what are they self-interested in. Is it food? Shelter? Money? Power? Love? Sex? It could be all of that, but none of that matters if it doesn’t make them better replicators. Evolution has been picking the best biological replicators for a long time. It turns out that having a brain that pursues and feels pleasure when it finds food, shelter, money, sex or power increases an individual replication success. Our world is now evolving at a much faster pace and our biology sometimes struggles to keep up. Some of our biological hard-coded pleasures often feel outdated as they can in-fact decrease our reproduction abilities. We now live in a world where companies provide us with high-caloric food, contraceptives, video games, porn and drugs that exploit our biological pleasures for profit. In fact, business plans are another type of replicator that consumes a common limited-resource (capital) in order to grow and replicate. It turns out that exploiting human biology is extremely profitable, and therefore, it leads to business plans that are good at self-replicating. So, we will be seeing more of those in the future.

Biological pleasure is a means to an end but not the end itself. Pursuing biological pleasure happens because on average it increases the replication success, when that stops being true the biological pleasures evolve to something else. Similarly, pursuing moral behaviour will increase the replication success of people and businesses. Amoral businesses may lose clients and investors, whilst amoral people may lose partners and friends. The higher the society’s education is on its values and ideology the more this will be true, as Elinor Ostrom (Nobel laureate) pointed out: when we share common notions of acceptable behaviour, we achieve order more efficiently than active policing. However, replicators that are able to trade-off moral behaviour for higher evolutionary fitness will eventually corrupt society. A moral business that pays its taxes will see its market share go to amoral competitors who rely on tax havens to evade taxes and reduce their product prices. Moral consumers may choose to stop buying products from tax-evading businesses and buy the more expensive moral alternative instead. Unfortunately, amoral people could secretly choose to purchase the cheaper products and save money for other useful things for self-replication. The system is starting to feel unstable. This is where the government kicks in. The role of the government is to enforce rules that make selfish behaviour equivalent to altruistic behaviour. Selfish behaviour equivalent to moral behaviour.

1st principle: The society-simulator should assume that its members are interested in self-replication (other interests will eventually go extinct), while its AI Ruler is interested in enforcing a certain value system.

How do Behaviours Spread?

Societies are defined by their people and businesses behaviours. Therefore, we are interested in studying how policies (also known as strategies) evolve.

A policy is a probabilistic distribution that tells us the probability of agent doing the action when in the state . You can think of it as the agent’s brain, where the state is the brain’s memory and perception of the world and the action is the brain’s command to the muscles. However, the concept also generalises to brainless and muscleless agents. Dependent on the field, policies are sometimes called strategies and actions are sometimes called behaviours. In our first example, the government increased the speeding tickets as a way to change drivers’ policies into assigning a higher probability for the behaviour of driving slower than the speed limit (where the speed limit is a part of the state) - this jargon can be quite confusing, so we will try to avoid it!

Genes are able to encode policies. Beavers removed from their parents at birth will build dams without ever being taught how to or seen others do it[3]. The dam-building policy is encoded in their genes and therefore it replicates in the same way as genes do. However, some other policies, like driving slower than the speed limit, spread by a completely different mechanism than the one used by genes. Both nature and nurture have an impact on one’s policies. It seems that the more efficient one’s brain is at learning, the highest is the impact of nurture in determining one’s policies. Nature was responsible for determining our biological pleasures because the pursuit of these pleasures (and avoidance of pain) during one’s lifetime is an efficient way to learn new policies whilst the genetic makeup remains static.

Ideas or behaviours that spread through non-genetic means such as writing, speech, and gestures can be called memes. The term was coined by Richard Dawkins in The Selfish Gene[4] and defined as the unit for carrying cultural ideas or practices that can self-replicate by being transmitted from one mind to another. The study of memes and its replication mechanisms was named memetics. As an example, through the lens of memetics, the success of religions can be explained by their members’ ability to hold and spread their beliefs. In fact, the promise of heaven to believers and hell to non-believers provides a strong incentive for members to retain their belief and convert others. Believers see conversions as saving non-believers’ souls from eternal damnation - a religious duty (selfish) and an altruistic act.

2nd principle: the society-simulator should focus on simulating policies: how they start, spread and die. This is complex, because policies replicate through people and businesses by different mechanisms which include genetics, memetics and business mechanisms.

The Society-Simulator

We now propose a framework for the society-simulator:

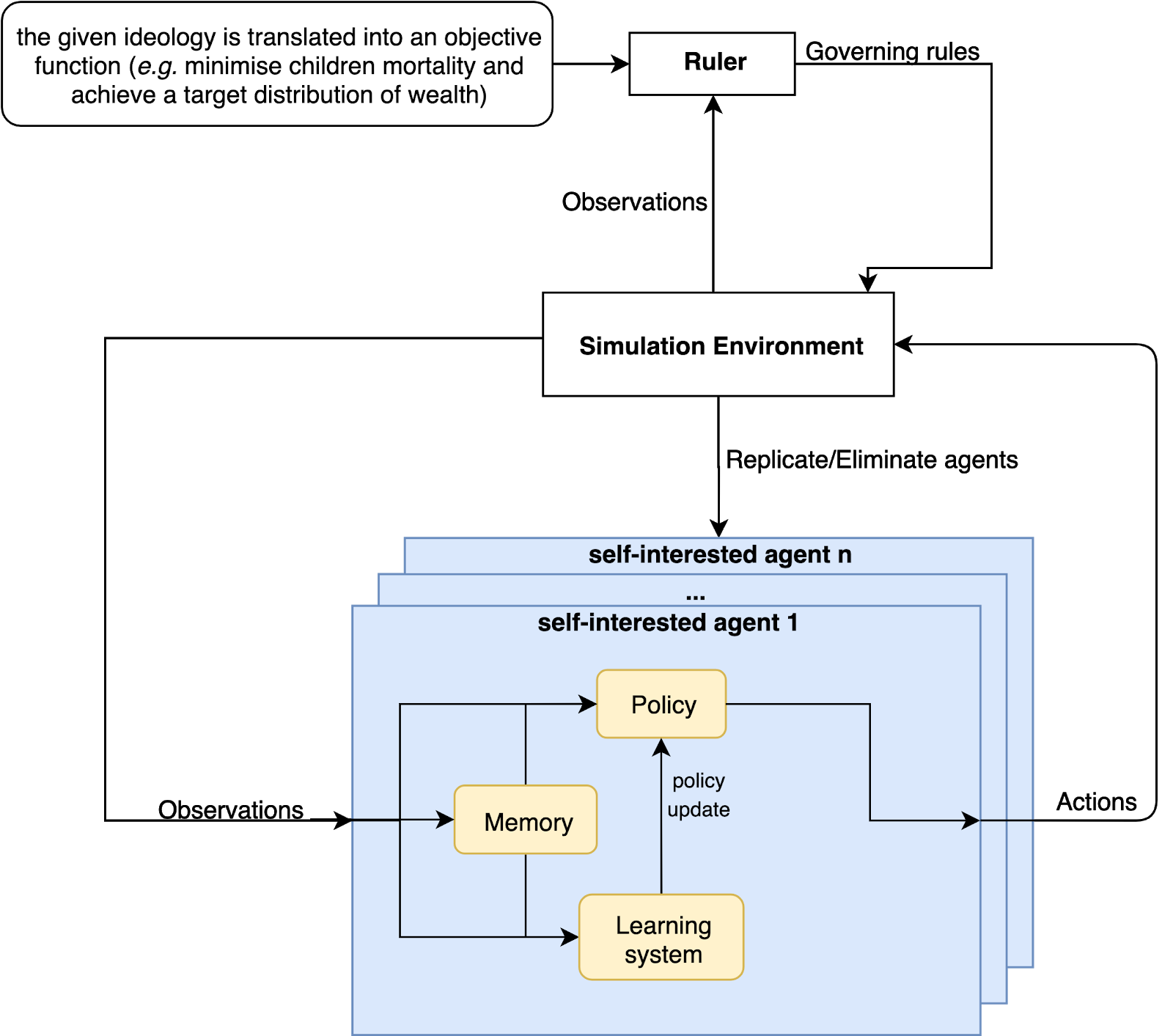

Our simulator is a multi-agent system with two types of entities: the Ruler (government) and the self-interested agents (citizens and businesses).

They live in a simulated environment that contains two types of rules:

- The static natural rules from physics and biology: how a citizen can move in the world, give birth, transform resources, build products, consume resources, die, and so on.

- The governing rules that provide incentives and penalties for certain behaviours, these include taxes, subsidies, fines, access to public infrastructures, and so on.

Citizens and businesses are born with adaptable policies and can interact with their virtual environment through an observation and an action space:

- Observation space: vision, internal state of the citizen (health, age, energy) or internal state of the business (employees, debt, profits), etc.

- Action space: move, trade, negotiate, mate, consume, etc.

The distribution of policies is naturally evolving: policies that are able to survive and spread will be a part of the future whilst the less capable policies disappear.

The Ruler attempts to drive the course of (policy) evolution by changing the governing rules. To do that we first need to translate society’s target ideology into an objective function such as: achieve the most uniform wealth distribution whilst maximising wealth per capita, life expectancy and citizen’s privacy. The Ruler’s task is to optimise the given objective function. It interacts with the world through its own observation and action space:

- Observation space: macro-statistics such as wealth distribution, tax evasion rate, population literacy, crime rates, etc.

- Action space: governing rules.

The framework will optimise both the governing rules ability to achieve a given ideology and the self-interested policies ability to spread. By doing so, we now have a way to search for the best set of governing rules able to produce an evolutionarily stable society; a society where policies that deviate from its ideology have an evolutionary disadvantage.

Final Words

To decide the right ideology to optimise we need to understand what people want. We already know that one: they want to survive and reproduce! Therefore, the right ideology is one that maximises its citizens ability to survive and reproduce. Also, rulers that don’t do this will see their population size decrease in comparison to other rulers, and will eventually disappear.

These ideas have motivated me to research ways to optimise multi-agent systems in open-ended evolutionary environments. It turns out that this is a very promising research area for general artificial intelligence (where general intelligence is defined as the intelligence demonstrated in animals, and specifically in humans). Our (mine and my co-authors’) research in this area resulted in a new algorithm that aligns learning with evolution: Evolution via Evolutionary Reward (EvER). We hope EvER will greatly speed up research in this area. In our experiments, we have used EvER to evolve bio-inspired agents in a bio-inspired environment and with it unravel a very interesting (and dark) evolutionary history. I have written a blog post about that here, and published a paper.

Would love to hear your opinion about society-simulators, send me an email or a message on twitter.

References:

[1] Romer, Paul. Technologies, rules, and progress: The case for charter cities. No. id: 2471. 2010.

[2] Friedman, Patri, and Brad Taylor. “Seasteading: Competitive governments on the ocean.” Kyklos 65.2 (2012): 218-235.

[3] Wilsson, Lars, and Joan Carroll Boone BULMAN. Bäver. My Beaver Colony. Translated… by Joan Bulman, Etc. Pan Books, 1970.

[4] Dawkins, Richard. The selfish gene, 1976.

[5] Smith, J. Maynard, and George R. Price. “The logic of animal conflict.” Nature 246.5427 (1973): 15.